United States District Court in Idaho voids numerous federal oil and gas leases in sage-grouse habitat areas within Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming, and sets aside corresponding Trump administration leasing procedures, while reinstating more stringent standards implemented during the Obama administration.[1]

In a win for environmentalists, a federal district court judge in Idaho voided 845 federal oil and gas leases in greater sage-grouse habitat areas issued in 2018 in Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming, finding Trump administration leasing policies are invalid. These leases and leasing policies, which were aimed at streamlining and simplifying the federal leasing process, were challenged as part of a broader effort to block drilling in habitat for the greater sage-grouse-an area that spans 67 million acres across 11 Western states.

In 2018, under the Trump administration, Bureau of Land Management (“BLM”)[2] leasing procedures changed with the implementation of the BLM’s Instruction Memorandum (“IM”) 2018-034. Western Watersheds Project and Center for Biological Diversity (collectively “WWP”), sued the BLM and the Secretary of the Interior in the federal district court in Idaho, asking the court to (1) vacate IM 2018-034 and, correspondingly, (2) vacate the leases issued under IM 2018-034. The State of Wyoming and oil and gas industry association Western Energy Alliance intervened in the action (collectively, with the BLM and Secretary of the Interior, referred to herein as “Defendants”).

Initially, the court entered a preliminary injunction requiring that, for oil and gas leases scheduled for the fourth quarter of 2018 and thereafter, the BLM must use procedures in the Obama-era instruction memorandum, IM 2010-117, and discontinue the use of conflicting procedures in IM 2018-034.[3] Thereafter, the court conducted a hearing to consider WWP claims that the Trump-era policy, IM 2018-034 (which affects environmental analysis of oil and gas leases), violates environmental law and revised previously existing BLM leasing processes without any public procedures (notice and comment) or environmental review.[4] The court issued its order as discussed below.

INVALIDATION OF IM 2018-034

Initially, the court concluded that IM 2018-034 is final agency action and thus subject to judicial review under the Administrative Procedures Act (“APA”). The court found that IM 2018-034 unequivocally replaces IM 2010-117, is effective immediately, and compliance therewith is mandatory,[5]being a final agency action, made up of both policy and rule.[6] Because it is subject to judicial review, the court next addressed whether it is procedurally and substantively valid.

To be procedurally valid, i.e. validly implemented, the court analyzed whether IM 2018-034 is a statement of policy that is exempt from requisite APA/FLPMA[7] notice-and-comment procedures. The court concluded IM 2018-034 is not a general statement of policy and, thus, is a substantive rule that should have been issued through notice-and-comment procedures, but was not. Therefore, IM 2018-034 was invalidly implemented.[8]

To be substantively valid, the terms of IM 2018-034 must be valid. The court concluded its terms improperly constrain public participation in BLM oil and gas leasing decisions. The court stated, “Public involvement in oil and gas leasing is required under FLPMA and NEPA,” and whether IM 2018-034 sufficiently allows for such public involvement “must be a complete ‘yes.’”[9] However, the court held IM 2018-034 does “not quite” allow sufficient public involvement under FLPMA and NEPA.[10]

Finally, apparently as an additional reason for invalidating IM 2018-034 for procedural deficiencies, the court stated, “[u]nder the APA, agency action may be set aside if it is arbitrary and capricious,”[11] and “[t]he agency’s administrative record reveals no analysis that would explain or justify the transition from IM 2010-117 to 2018-034 and the resulting curtailment of the public’s involvement in oil and gas leasing decisions on public land.”[12] Thus, the court concluded IM 2018-034’s issuance was arbitrary and capricious.[13] “Faster and easier lease sales, at the expense of public participation, is not enough.”[14]

Based on the foregoing, the court set aside IM 2018-034’s at-issue provisions and IM 2010-117’s corresponding provisions were reinstated until the BLM completes a prior notice-and-comment rulemaking to govern its lease review process.[15]

INVALIDATION OF LEASE SALES IN SAGE-GROUSE HABITAT MANAGEMENT AREAS

The parties do not dispute that the BLM applied IM 2018-034 in approving the “Phase One Lease Sales,” more particularly described as the following lease sales:

- June 2018 Wyoming

- June 2018 Nevada

- September 2018 Wyoming

- September 2018 Nevada

- September 2018 Utah

Defendants essentially argue “no harm no foul,” claiming that, despite application of IM 2018-034 to the Phase One Lease Sales, WWP was not prevented from submitting substantive comments on the sales and WWP, in fact, did so.[16] The court was unconvinced, stating that, “with more time to comment on the Phase One Lease Sales, WWP and other organizations would have more meaningfully participated in the process and, relatedly, put BLM on notice.”[17] “Yet, not being allowed to participate at the leasing stage, or in having to hurriedly clamber to do so because of IM 2018-034’s condensed comment and protest periods, oil and gas leases have been issued without the full benefit of public input.”[18]

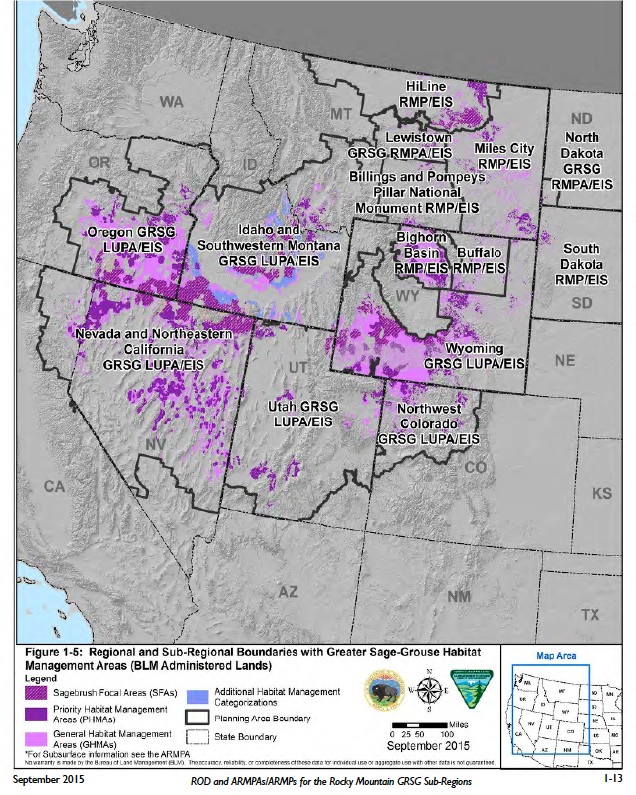

Although the court rejected Defendants’ “no harm no foul” argument, the court did limit the impact of its decision to those oil and gas leases that affect greater sage-grouse habitats.[19] The court concluded, “a nationwide directive to all oil and gas lease sales throughout the United States, without regard to whether such lease sales implicate sage-grouse habitat, is not justified.”[20] “Therefore, the remedy here – setting aside certain of IM 2018-034’s provisions in favor of IM 2010-117’s – applies to oil and gas lease sales contained in whole or in part within the Sage-Grouse Plan Amendments’ recognized ‘Planning Area Boundaries’ encompassing ‘Greater Sage-Grouse Habitat Management Areas,’ as indicated in the following BLM Map: ”[21]

IM 2010-117 was thus reinstated by the court, but its application was limited to areas within the Planning Area Boundaries identified in the foregoing map.

PHASE ONE LEASE SALES SET ASIDE AND PRELIMINARY INJUCTION APPLYING TO SUBSEQUENT LEASE SALES CONFIRMED

Based on the foregoing, the court set aside the Phase One Lease Sales, stating that “setting aside the Phase One Lease Sales will not be so disruptive as to merit an exception from the standard remedy of vacatur.”[22] Based on the court’s holding, each of the Phase One Leases presumably is contained in whole or in part within the Planning Area Boundaries, but we have not separately confirmed this fact. The WWP identified in its complaint the specific leases issued under these sales, which list we have attached hereto.

The court also addressed the previously entered preliminary injunction, which applied the Obama standards to sales scheduled for the fourth quarter of 2018 and thereafter, determining that the rationale behind issuing the preliminary injunction remains solid. As such, the court likewise entered partial summary judgment in WWP’s favor in that respect.[23]

CONCLUSIONS

The Western Energy Alliance indicated that it plans to appeal and the State of Wyoming will be doing so as well. They are coordinating with the BLM and Department of Justice to determine their response. Among the criticisms of the order are that the Obama standards, IM 2010-117, likewise failed to undergo any notice-and-comment rulemaking, as is the nature of Instruction Memorandums, and that the judge in this case simply preferred one to the other.

The following pages contain a list of leases relevant to this order, as identified in WWP’s Second Amended Complaint. This list includes the following categories of leases:

1. Phase One Lease Sales (sales from the June and September 2018 lease sales in Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming) which, as discussed above, were specifically set aside by the court’s order. It is not clear whether there were other lease sales during these June and September 2018 periods that might implicate sage-grouse habitat.

2. Lease sales for the fourth quarter of 2018 and the first quarter of 2019. The court indicates that, in accordance with its preliminary injunction, the BLM postponed upcoming December 2018 lease sales in sage-grouse habitats to follow the Obama procedures contained in IM 2010-117. Accordingly, the court did not specifically set aside these “post-Phase One Leases” (as we have identified them in the following list). Presumably, if such leases have been issued, they were issued in accordance with IM 2010-117. However, we have not confirmed this information, and it will need to be separately investigated. We also have not confirmed that the attached list, which was obtained from WWP’s complaint, includes all federal oil and gas leases in sage-grouse habitats issued in the last quarter of 2018 and thereafter.

3. Various lease sales in 2017 and 2018 prior to the second quarter of 2018. These “pre-Phase One Leases” (as we have identified them in the following list) were outside the scope of the court’s order (which addressed pending motions pertaining to IM 2018-034 under WWP’s Fourth and Fifth Claims for Relief). Nevertheless, the validity of these pre-Phase One leases is still at issue in the action and yet to be decided. Because these “pre-Phase One Leases” were not addressed in the court’s order, we have not investigated the nature of the claims surrounding these leases, nor have we confirmed that it is an exhaustive list of leases that might be implicated by WWP’s remaining claims.

For your convenience, we have separately identified/categorized the pre-Phase One Leases, Phase One Leases, and post-Phase One Leases.

[1] Western Watersheds Project, & Center for Biological Diversity v. Ryan K. Zinke, Sec’y of Interior; David Bernhardt, Deputy Sec’y of Interior; & United States Bureau of Land Management, & State of Wyoming; Western Energy Alliance, No. 1:18-CV-00187-REB, 2020 WL 959242, at *1 (D. Idaho Feb. 27, 2020).

[2] The BLM being the federal agency handling leasing of federal oil and gas interests.

[3] Id. at *2.

[4] Id. at *3. The court did not address arguments as to another instruction memorandum, IM 2018-026, apparently because this applied to other Claims for Relief and the pending “partial” summary judgment motions pertained specifically to IM 2018-034. See id.

[5] Id. at **3, 10, 11.

[6] Id. at *27.

[7] Federal Land Policy and Management Act of 1976.

[8] Id. at *15.

[9] Id.

[10] National Environmental Policy Act.

[11] Id. at *18 (citing 5 U.S.C. § 706(2)(A)).

[12] Id. at *20.

[13] Id.

[14] Id.

[15] Specifically: for all succeeding oil and gas lease sales, (1) use of IM 2018-034, Section III.A – “Parcel Review Timeframes” is enjoined and replaced with IM 2010-117, Section III.A – “Parcel Review Timeframes;” (2) use of IM 2018-034, Section III.B.5 – “Public Participation” is enjoined and replaced with IM 2010-117, Section III.C.7 – “Public Participation;” (3) use of 2018-034, Section III.D. – “NEPA Compliance Documentation” is enjoined and replaced with IM 2010-117, Section III.E – “NEPA Compliance Documentation;” and (4) use of IM 2018-034, Section IV.B – “Lease Sale Parcel Protests” is enjoined and replaced with IM 2010-117, Section III.H – “Lease Sale Parcel Protests.”

[16] Id. at **20-21.

[17] Id. at *25.

[18] Id.

[19] Western Watersheds Project, 2020 WL 959242 at *27.

[20] Id.

[21] Id. at *28.

[22] Id. at *30 (“Instead, because of the violations already welded into the Phase One Lease Sale process, vacatur here will avoid harm to the environment and further the purposes of NEPA and FLPMA.”)

[23] Id. at *2.