Federal oil and gas leases are administered by the Bureau of Land Management (“BLM”) pursuant to the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920, as amended (“MLA”), and the implementing federal regulations. Federal leases have a slightly different ownership scheme than fee oil and gas leases. As to fee leases, the lessee owns a leasehold interest that includes the right to drill for and produce the leased substances, subject to royalty payments to the lessor. The term “working interest” is commonly used and is generally considered synonymous with the lessee’s interest and the term “leasehold interest.” As to federal leases, the lessee’s leasehold interest includes both record title and operating rights. Initially, these two types of interests are merged together as the record title interest, but the operating rights interest can be severed from the record title interest by assignment. The record title interest includes the obligation to pay rent and the rights to assign and relinquish the lease.[1] The operating rights interest authorizes the holder to drill for and conduct operations and produce the leased substances.[2] When all or a portion of the operating rights have been severed from the record title, the operating rights interest owner is primarily liable for its pro rata share of payment obligations under the lease while the record title interest owner is secondarily liable.[3] At the extreme, if all of the operating rights as to all depths are severed by assignment from the record title interest, the lessee owns “bare” record title interest and has no rights to drill for and produce the leased substances. The term “working interest” is generically associated with the operating rights interest unless said operating rights interest has not been severed from the record title interest, then it is associated with the record title interest. Otherwise, the range of interests that may be created out of federal leases is nearly the same as fee leases.

The interests in federal leases are generally conveyed by a “transfer,” being defined in the federal regulations as “any conveyance of an interest in a lease by assignment, sublease or otherwise.”[4] Set forth below is a discussion of the different types of interests that may be transferred in federal leases and whether the instrument transferring the interest must be filed with and approved by the BLM.[5]

Record Title Interests

The MLA and federal regulations use the term “assignment” for a transfer of all or a portion of the lessee’s record title interest in a lease.[6] All assignments of record title interests must be on the currently approved BLM form Assignment of Record Title Interest in a Lease for Oil and Gas or Geothermal Resources, Form 3000-003.[7] Record title interests may be transferred as to all or part of the acreage in the lease or as to either a divided or undivided interest therein.[8] Record title interests may not be transferred as to limited depths or horizons, separately as to either oil or gas, less than part of a legal subdivision,[9] or less than 640 acres (outside of Alaska).[10]

Upon receipt of the assignment, the BLM will engage in an “adjudication” process whereby the BLM will determine and identify the owners of interests and their percentage interest in the lease as a consequence of the assignment and approve the assignment if it meets all statutory and regulatory requirements. The rights of the assignee will not be recognized by the BLM until the assignment has been approved.[11]

Operating Rights Interests

The MLA and federal regulations use the term “sublease” for a transfer of a non-record title interest in a lease, including a transfer of operating rights. All transfers of operating rights interests must be on the currently approved BLM form Transfer of Operating Rights (Sublease) in a Lease for Oil and Gas or Geothermal Resources, Form 3000-3a.[12] For transfers of operating rights interests, the MLA and federal regulations do not contain any limitations on such transfers other than it must be as to “all or part of the acreage in the lease.”[13]

Upon receipt of the transfer, the BLM will engage in the adjudication process to determine and identify the owners of interests and their percentage interest in the lease as a consequence of the transfer and approve the assignment if it meets all statutory and regulatory requirements. The rights of the transferee will not be recognized by the BLM until the transfer has been approved.[14] However there was a period of time where most state offices of the BLM did not adjudicate transfers of operating rights.

Beginning in 1985, the BLM issued internal guidance, Washington Office Instruction Memorandum No. 1986-175 (Dec. 30, 1985) (“IM 1986-175”), stating that it was not necessary for the BLM to “adjudicate” operating rights assignments[15] on the grounds that they are third-party contracts. The BLM adjudicators were instructed to stop adjudicating operating rights transfers, and to instead “rubber stamp” them within 30 days of their submission when there was no “evidence to the contrary regarding qualifications and proper bonding.”[16] Accordingly, most BLM offices began accepting transfers of operating rights and “approved” the transfers without confirming and determining the ownership of the operating rights interests. In 2013, the BLM issued Instruction Memorandum No. 2013-105 (April 4, 2013) (“IM 2013-105”), directing all BLM offices to immediately begin again adjudicate transfers of operating rights interests.[17] Understanding that there would be a backlog to carry this out this directive, IM 2013-105 provides a priority schedule for adjudicating existing and future transfers of operating rights as follows: if first production occurs on or after October 1, 2012, adjudicate all transfers of operating rights immediately; if first production occurred prior to October 1, 2012, adjudicate as necessary to enable the Office of Natural Resources Revenue (“ONRR”) to issue appropriate orders to the owners; and adjudicate all remaining unadjudicated operating rights transfers when time and staffing allows.

Obviously, the BLM offices are faced with trying to adjudicate and determine the current operating rights interest owners based on over thirty years of potentially incomplete and possibly erroneous transfers contained in the BLM lease files. A survey was conducted in 2017 of the following BLM State Offices to determine how they were implementing IM 2013-105 and adjudicating transfers of operating rights.[18]

Colorado

For leases occurring prior to 2012, the Colorado State Office is only conducting reviews for leases with production at the request of ONRR. When it discovers discrepancies, it considers those transfers null and void from their inception and does not provide or send out unapproved operating rights decision letters because the transfers were never adjudicated. Colorado is not willing to accept county records or other outside sources to assist in curing title deficiencies. For leases occurring after October 1, 2012, the Colorado Office will adjudicate all transfers accordingly.

Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Utah[19]

The Montana and Utah State Office never stopped adjudicating transfers of operating rights; accordingly, IM 2013-105 did not change how they are adjudicating such transfers.

New Mexico, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas[20]

The New Mexico State Office is conducting a piecemeal review of its lease files. Initially, when the New Mexico State Office received a new assignment and could not account for the purported interest to be assigned, they retroactively denied previously approved transfers either (a) all the way back until the title examiner could account for the purported interest; or (b) through 1991. It appears that recently, the New Mexico State Office has become willing to consider outside records in examining title to fill in gaps in currently filed assignments, such as recorded assignments, evidence of corporate successions, etc.

Wyoming

The Wyoming State Office adjudicates operating rights for all new leases, as well as any adjudications requested by ONRR. It also has plans to adjudicate operating rights for all producing leases according to staff availability. The Wyoming State Office is currently using the Lease Interest Worksheet to chain title retroactively and adjudicate operating rights at the request of the ONRR. During this review, and when any new transfer is filed, if the State Office examiner cannot account for the purported interest to be assigned, they stamp the Lease Interest Worksheet “discrepancy.” Thereafter, the Wyoming State Office will not approve any subsequent transfer until the problem in the chain of title is resolved. No notice of the discrepancy is provided to the parties who received interests through transfers now marked with a discrepancy, so without review of the current BLM case file for each lease or subsequently denied transfer, parties who believed they previously owned operating rights are not aware their rights have been called into question. This requires the Wyoming State Office to deny any subsequent transfers for leases containing a discrepancy, and to disregard any assignments occurring before the discrepancy that were previously approved.

In an attempt to complete a chain of title, bring current its files, and resolve any discrepancies, the Wyoming State Office is accepting a certified copy of an assignment recorded in the county records and attached to a BLM form Transfer of Operating Rights that is completed by general references to the attached county assignment. The Wyoming State Office will issue a decision stating that its records are incomplete and in order to complete its records, it is accepting and approving the assignment.

Overriding Royalty Interests, Production Payments, and Other Interests

The federal regulations make specific reference to only two other types of interests, overriding royalty interests and production payments.[21] Transfers of these interests must be filed with the BLM and will be included in the lease file, but are not subject to BLM approval.[22] While they can be filed on either a BLM form assignment,[23] any form of assignment may be used.

While net profits interests and carried interests are not expressly mentioned in the regulations governing assignments of interests, such interests are included in the definition of “interest.”[24] The usual practice is to follow the same filing procedures prescribed from assignments of overriding royalty interests and production payments above.

Liens and Security Interests under Mortgages and Other Financing Instruments

Liens and security interests in federal leases created under mortgages and other financing instruments do not fall within the definition of “interests” under the regulations and are not required to be accepted for filing under the regulations. Most BLM offices will discourage or even reject the filing of mortgages and other financing instruments. As a result, mortgages and other financing instruments are typically only filed in the county records.

Transfers by Operation of Law

The regulations identify two types of transfers by operation of law: death and corporate reorganization. When an owner dies, his or her rights will be recognized as having been transferred to the heirs, devisees, executor, or administrator of the estate, upon the filing of a statement that all parties are qualified to hold an interest in a federal lease.[25] The BLM office will typically also require, along with the statement, supporting information concerning the demise of the owner.

In the case of corporate name change, merger, or conversion, no assignment is required unless otherwise required by state law. The regulations require that notification of the name change, merger, or conversion be furnished in the proper BLM office.[26]

_____________________

Prior to filing any transfer with the BLM, it is always to the advantage of the parties to the transfer to make inquiry of the oil and gas adjudication personnel at the applicable BLM office to confirm that the parties have prepared the transfer in compliance with the office’s policies and procedures.

[1] 43 CFR § 3100.0-5(c). Record title is the ownership in a federal lease as recognized by the BLM. Therefore, it has no connection to the title or leasehold ownership reflected in the applicable county records.

[2] 43 CFR § 3100.0-5(d). The term “operating rights” should not be confused with the right to serve as operator on the ground. An operator is the person or entity that is responsible under the terms and conditions of the lease for operations being conducted on the leased lands; it can include, but is not limited to, the lessee record title interest owner or operating rights interest owner. See 43 CFR § 3160.0-5

[3] See 43 CFR §§ 3106.7-6(b), 3216.12.

[4] Id. § 3100.0-5(e).

[5] Not addressed herein are the qualifications to own an interest in a federal lease and the specific filing requirements.

[6] Id. § 3100.0-5(e).

[7] Most recent revision date is August 1, 2015.

[8] Id. § 3106.1(a). Note, the assignment of the entire interest in a portion of the leasehold will result in a segregation of the lease.

[9] Generally, requiring all of a governmental lot or quarter-quarter section under the Public Land Survey System.

[10] 30 USC § 1987a; 43 CFR § 3106.1. The 640 acre limitation was added to Section 30A of the MLA in 1987 pursuant to the Federal Oil and Gas Onshore Leasing Reform Act. Assignments of record title of less than 640 acres will be approved if the assignment constitutes the entire lease or is demonstrated to further the development of oil and gas.

[11] 43 CFR § 3106.1(b).

[12] Most recent revision date is August 1, 2015.

[13] 43 CFR § 3106.1. There is no written guidance defining “part of the acreage” or addressing this apparent acreage requirement. It appears that at least some minimal amount of acreage must be transferred to comply. Accordingly, although some BLM State offices will accept transfers of operating rights for less than 40 acres, they will not accept for approval, or even for filing purposes only, transfers of operating rights in a wellbore only.

[14] Id. § 3106.1(b).

[15] The term “assignment” is used generically in the IM applying to an assignment of either a record title interest or an operating rights interest.

[16] IM 1986-175.

[17] IM 2013-105 was issued in direct response to the 1996 amendment to Section 102(a) of the Federal Oil and Gas Royalty Management Act, 30 USC § 1712(a), providing that the owner of the operating rights shall be primarily liable for its pro rata share of payment obligations under the lease and the owner of the record title interest (if different from the owner of the operating rights interest) became secondarily liable. The federal regulations at 43 CFR Section 3016.7-6 and 3216.12, reflect these same principals. Furthermore, the BLM form Transfer of Operating Rights (Sublease) in a Lease for Oil and Gas or Geothermal Resources specifically provides that the transferee’s signature “constitutes acceptance of all applicable terms, conditions, stipulations, and restrictions pertaining to the lease… (Part B, paragraph 3) and “upon approval of a transfer of operating rights (sublease), the sublessee is responsible for all lease obligations under the lease rights transferred to the sublessee” (Part C, paragraph 8).

[18] See Jared A. Hembree and Uriah J. Price, Holding a Wolf by the Ears – A Look into BLM’s Policy on the Retroactive Adjudication of Operating Rights, 63 Rocky Mt. Min. L. Inst., Paper 11 (2017) (not yet published).

[19] The Montana State Office administers federal lands in Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota. The Utah State Office administers federal lands in Utah only.

[20] The New Mexico State Office administers federal lands in New Mexico, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas.

[21] 43 CFR § 3106.1.

[22] 43 CFR § 3106.1(b).

[23] Both of the current BLM forms include a box that can be checked to indicate that it is for an overriding royalty interest assignment.

[24] 43 CFR § 3000.0-5(1).

[25] Id. § 3106.8-1.

[26] Id. § 3106.8-3.

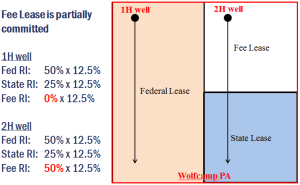

So what happens if the lessee’s working interest is committed to the unit agreement, but the lessor’s royalty interest is not? While the lessee will be allocated proceeds according to its proportionate share of the unit production area, the lessor will be allocated proceeds on a leasehold basis. This can result in a windfall either for the lessor or the lessee (compare the allocation of proceeds from the 1H and 2H wells in the diagram to the right, assuming 320 acre standup spacing units).

So what happens if the lessee’s working interest is committed to the unit agreement, but the lessor’s royalty interest is not? While the lessee will be allocated proceeds according to its proportionate share of the unit production area, the lessor will be allocated proceeds on a leasehold basis. This can result in a windfall either for the lessor or the lessee (compare the allocation of proceeds from the 1H and 2H wells in the diagram to the right, assuming 320 acre standup spacing units).